By: Juan Manuel Orjuela, MD

Neuropsychiatrist

Epilepsy and depression are two complex neurological conditions that, despite their distinct characteristics, often intersect, creating unique challenges for individuals affected by both. Epilepsy, a disorder marked by recurrent seizures, arises from abnormal electrical activity in the brain, while depression, a mood disorder, impacts one’s emotional well-being and overall quality of life (QOL).

Approximately 50 million people are living with epilepsy worldwide. People with active epilepsy are estimated to make up a proportion of the general population of between 4 and 10 per 1000 people. People with epilepsy have a high prevalence of depression and consequently comorbid psychiatric problems, ranging from 11% to 63%1.

Multiple studies have reported negative impacts of depression on QOL and seizure control and increased use of medical services by patients with epilepsy, as well as a rise in costs for caring for those patients. Moreover, depression has been associated with higher rates of drug resistance in patients with epilepsy. In fact, it has been suggested that the relationship between epilepsy and depression is bidirectional; having epilepsy would increase the risk of depression, and having depression appears to increase the risk of epilepsy. Patients with epilepsy and depression have a high rate of suicide, underscoring the imperative for accurate detection of this comorbidity to provide the best treatments available2.

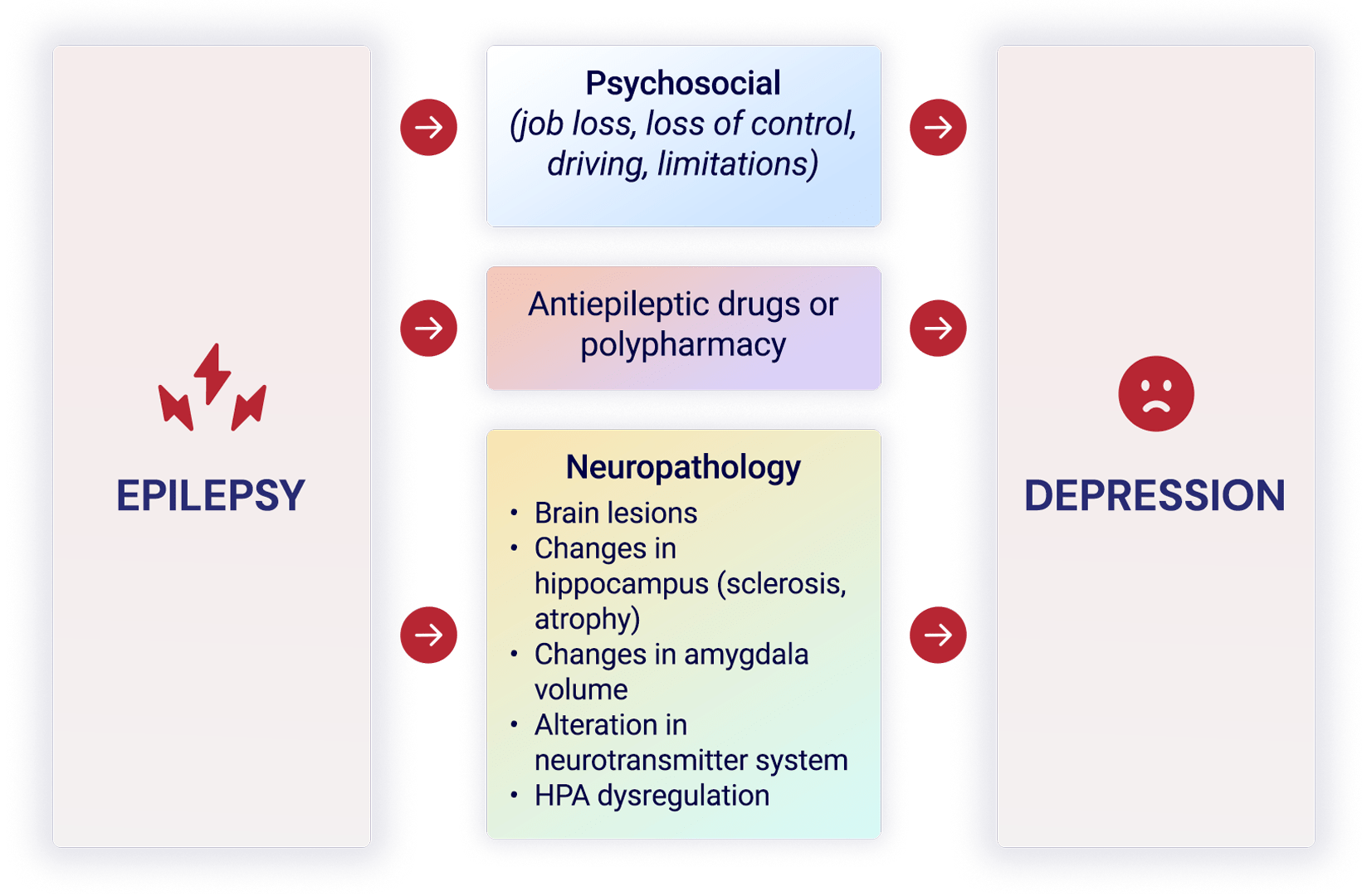

The Hermann and Whitman model hypothesizes that the genesis of depression in epilepsy is due to the following three main factors: those related to the brain, factors with neurobiological characteristics shared by depression and epilepsy; those related to treatment, i.e., factors caused by depressogenic antiepileptic drugs, such as tiagabine, vigabatrin, topiramate, and phenobarbital; and those unrelated to the brain, i.e., environmental and psychosocial factors, such as stigma and social discrimination and patients’ use of maladaptive strategies (e.g., nonacceptance of the disease) 3 (Figure 1).

Globally, close to 80% of people living with epilepsy who live in low- and middle-income countries may not receive treatment. The International League against Epilepsy (ILAE) and International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) have globally initiated epilepsy projects with the slogan “Out of the Shadows” as a global campaign since 1997. Reducing the Epilepsy Treatment Gap and the Mental Health Gap Action Program (MH GAP) have already been implemented in Ghana, Mozambique, Myanmar, and Vietnam as WHO programs1. Treatment must be carried out comprehensively. It is recommended to attend to the epileptologist to adjust the dose of antiepileptic medications and improve seizure control. On the other hand, it is known that some antiepileptic medications can improve mood, for example, valproic acid and lamotrigine, so it is recommended to suggest it to the treating doctor.

It is essential to start a psychotherapeutic process, if possible, with a cognitive behavioral approach, since it is the one that has shown the best evidence in this population. In this process, the reduction of personal and social stigma is addressed, self-esteem is also strengthened, and the acceptance of the disease is crucial. It is also important to start antidepressant medications to optimize brain function affected by the disease. The use of serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (sertraline, escitalopram) or dual antidepressants such as desvenlafaxine can be excellent options for this population, due to their effectiveness, tolerance, and poor interactions with other medications4.

In conclusion, reducing stigma surrounding epilepsy and depression is essential for fostering a more inclusive and supportive environment for those affected by these conditions. By promoting education, empathy, and understanding, along with advocating for policy changes and providing adequate support systems, we can work towards a society where individuals with epilepsy and depression receive the respect, dignity, and effective treatment they deserve.

- Mar Htwe Z, Lae Phyu W, Zar Nyein Z, Aye Kyi A. Correlation between depression and perceived stigma among people living with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2023 Sep;146:109372. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109372. Epub 2023 Aug 4. PMID: 37542748.

- Orjuela-Rojas JM, Martínez-Juárez IE, Ruiz-Chow A, Crail-Melendez D. Treatment of depression in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy: A pilot study of cognitive behavioral therapy vs. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Epilepsy Behav. 2015 Oct;51:176-81. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.07.033. Epub 2015 Aug 16. PMID: 26284748.

- Alhashimi R, Thoota S, Ashok T, Palyam V, Azam AT, Odeyinka O, Sange I. Comorbidity of Epilepsy and Depression: Associated Pathophysiology and Management. Cureus. 2022 Jan 23;14(1):e21527. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21527. PMID: 35223302; PMCID: PMC8863389.

- Maguire MJ, Marson AG, Nevitt SJ. Antidepressants for people with epilepsy and depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Apr 16;4(4):CD010682. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010682.pub3. PMID: 33860531; PMCID: PMC8094735.

- Alhashimi R, Thoota S, Ashok T, et al. Comorbidity of Epilepsy and Depression: Associated Pathophysiology and Management. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21527. Published 2022 Jan 23. doi:10.7759/cureus.21527